Bone injuries and disorders have been part of human life for as long as we have existed. From simple fractures caused by falls to complex bone loss following trauma, tumors, or infections, orthopedic treatments have continuously evolved to restore mobility and quality of life. For decades, surgeons have relied on bone grafts, metal implants, and ceramic substitutes to repair damaged bones. These approaches have saved countless lives and improved function for millions of patients.

However, as medical science advances, expectations are changing. Today, it is no longer enough for a material to simply “fill a gap” or “hold things together.” Modern orthopedic solutions are expected to actively participate in healing. This is where bioactiveglass is transforming the landscape.

In this blog, we will explore how traditional orthopedic methods work, where their limitations lie, and how bioactiveglass is emerging as a scientifically backed, clinically promising material that supports natural bone regeneration in a smarter way.

Understanding Bone Healing in Orthopedic Treatment

Before diving into materials, it is important to understand how bone naturally heals.

Bone is a living tissue. When a fracture occurs, the body immediately begins a well-coordinated repair process:

- Inflammation phase – Blood clot forms and healing cells gather.

- Repair phase – New bone tissue (callus) starts forming.

- Remodeling phase – Bone reshapes and strengthens over time.

For small fractures, the body can heal on its own with proper alignment and stability. But in cases of:

- Large bone defects

- Severe trauma

- Tumor removal

- Spinal fusion procedures

- Chronic infections like osteomyelitis

…the body needs support. This is where orthopedic materials come in.

Traditional Orthopedic Solutions

1. Autografts: The Gold Standard

Autografts involve taking bone from one part of the patient’s body (often the hip) and placing it into the damaged area.

Why they work well:

- They contain living bone cells.

- They provide natural biological signals.

- They offer a scaffold for new bone growth.

Autografts are considered ideal because they support bone formation in three important ways:

- Osteogenesis (living cells form new bone)

- Osteoinduction (signals stimulate bone growth)

- Osteoconduction (structure supports bone growth)

But there are drawbacks:

- Limited supply of bone.

- Additional surgery required.

- Pain and risk at the donor site.

- Longer recovery time.

For large defects or elderly patients, autografts are not always practical.

2. Allografts: Donor Bone

Allografts come from human donors and are processed in bone banks.

Advantages:

- No second surgery for the patient.

- Available in larger quantities.

- Useful in trauma and reconstructive orthopedic procedures.

Limitations:

- Reduced biological activity after sterilization.

- Slower integration into the patient’s bone.

- Small risk of immune reaction or disease transmission.

- Primarily act as a scaffold rather than actively stimulating bone growth.

3. Synthetic Ceramics

Materials like hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate are commonly used in orthopedic applications.

These ceramics:

- Resemble the mineral component of bone.

- Are biocompatible.

- Provide structural support.

However, most traditional ceramics are biologically passive. They allow bone to grow on them but do not actively stimulate regeneration. Additionally, they can be brittle and may not degrade in sync with natural healing.

4. Metal Implants

Plates, screws, rods, and joint replacements are widely used in orthopedic surgeries.

Metals such as titanium provide:

- High strength.

- Immediate load-bearing capacity.

- Long-term durability.

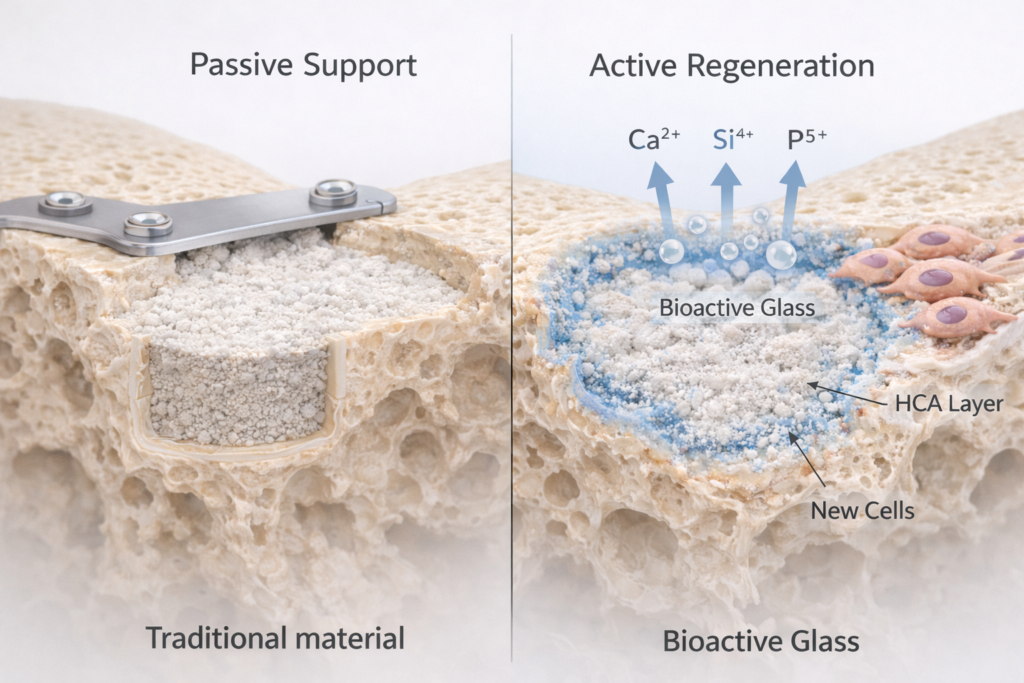

But metals are inert. They stabilize the bone but do not encourage biological healing. In some cases, stress shielding can occur, where the implant takes too much load, weakening surrounding bone.

The Need for Smarter Materials in Orthopedic Care

Modern orthopedic challenges go beyond mechanical repair. Surgeons increasingly seek materials that can:

- Stimulate natural bone regeneration.

- Reduce infection risk.

- Integrate seamlessly with host tissue.

- Adapt to patient-specific conditions.

- Support long-term remodeling.

This shift has led researchers to explore materials that interact with the body rather than simply existing inside it.

That is where bioactiveglass stands apart.

What is Bioactiveglass?

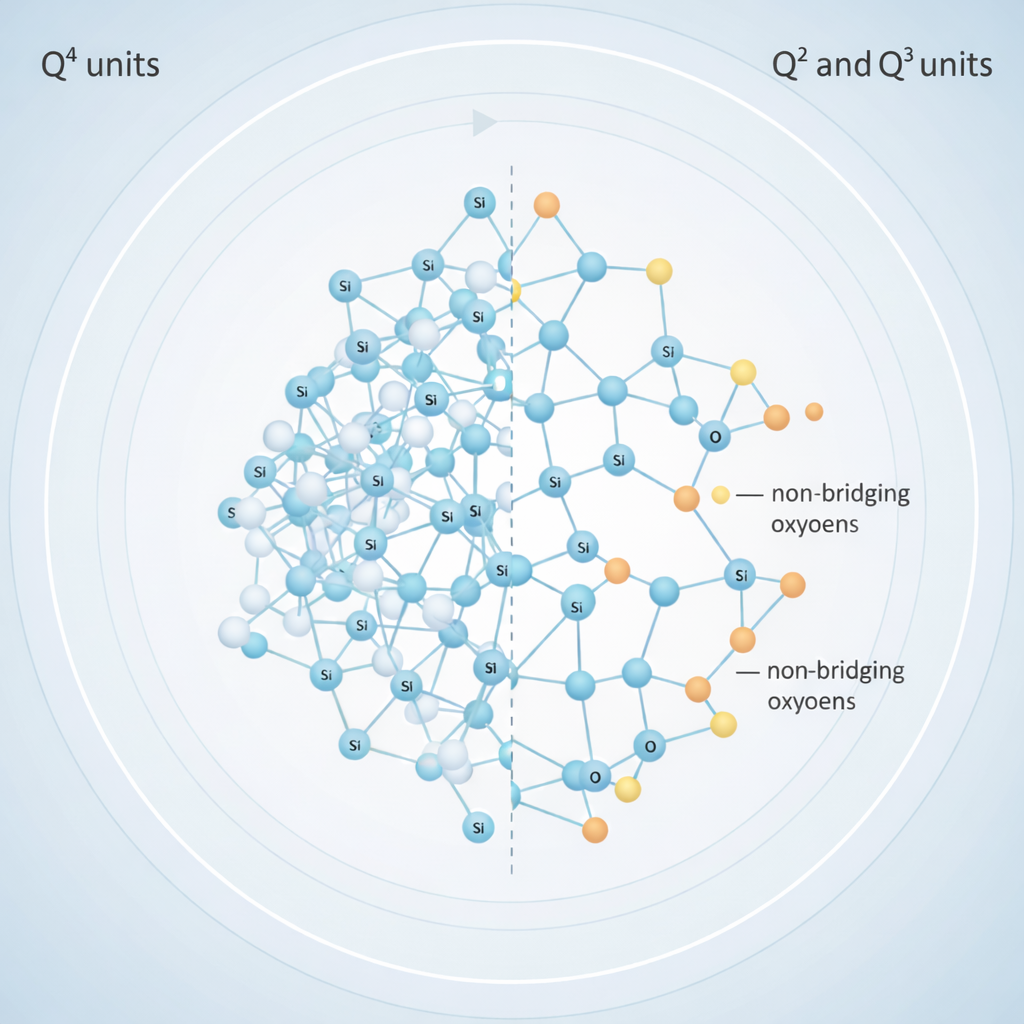

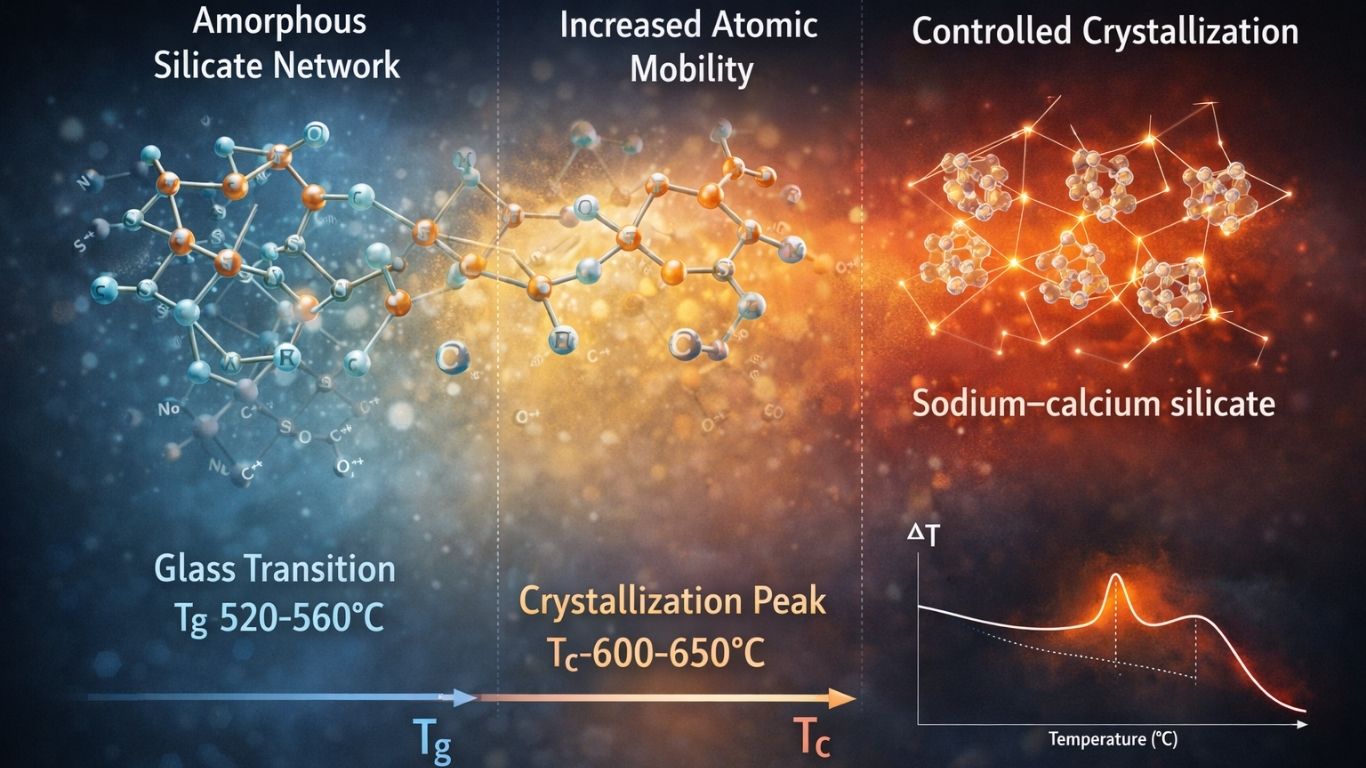

Bioactiveglass is a specially designed silica-based material first developed in the late 1960s by Professor Larry Hench. Unlike traditional materials that remain passive in the body, bioactiveglass reacts with body fluids in a controlled and beneficial way.

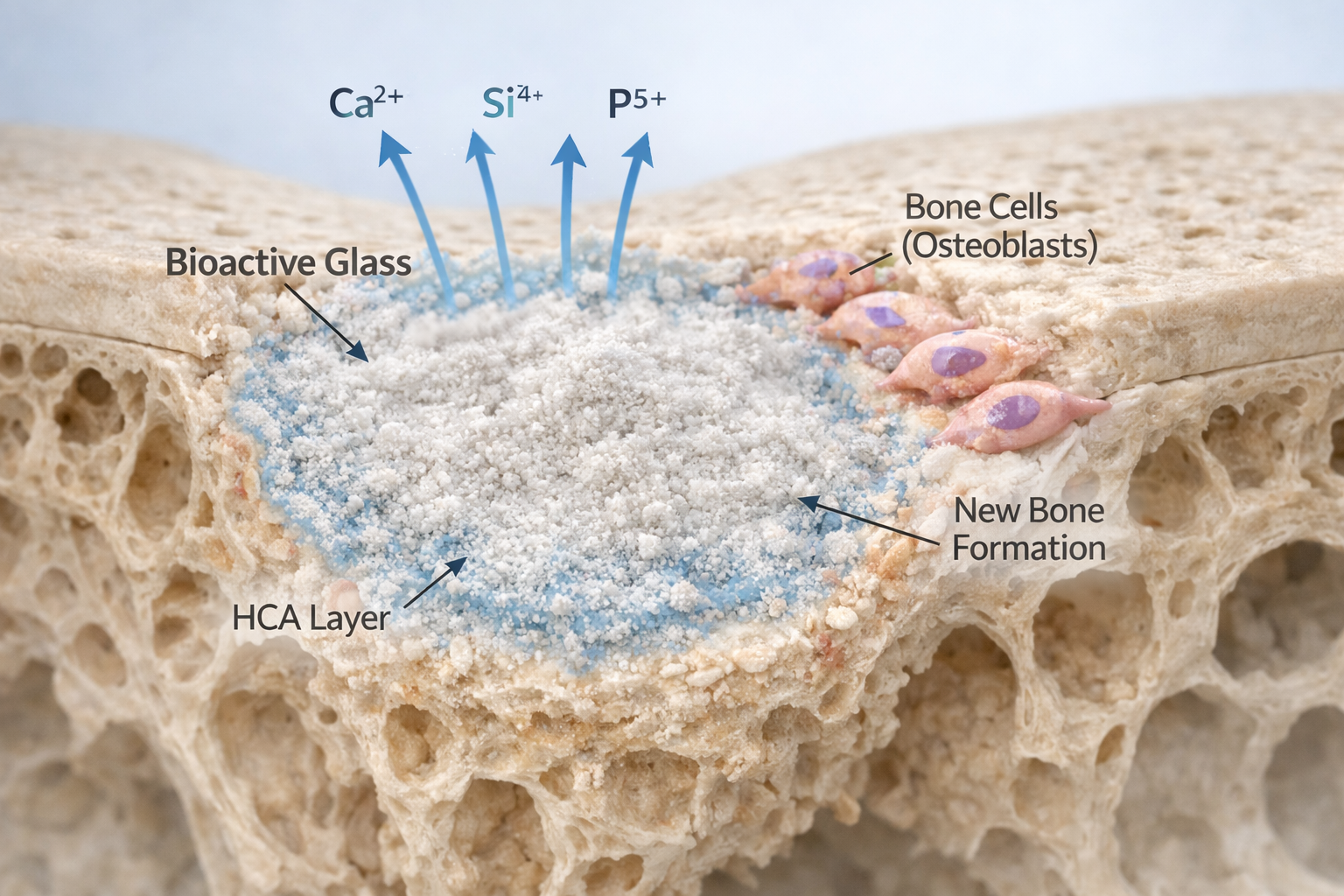

When implanted into bone, it does something remarkable:

It forms a layer on its surface that closely resembles natural bone mineral. This layer, known as hydroxycarbonate apatite (HCA), allows the material to bond directly with living bone.

Instead of acting as a filler, bioactiveglass becomes part of the healing process.

How Bioactiveglass Works in the Body

The science behind bioactiveglass is well documented in biomaterials research.

When it comes in contact with body fluids:

- Ion exchange begins – Sodium and calcium ions are released.

- Silica-rich layer forms – The surface reorganizes.

- Calcium-phosphate layer develops.

- Hydroxycarbonate apatite forms – Similar to natural bone mineral.

This final layer enables direct bonding with bone tissue.

But the process does not stop there.

The released ions (calcium, silicon, phosphorus) play a biological role. Research shows these ions can:

- Stimulate osteoblast activity (bone-forming cells).

- Encourage cell proliferation.

- Support gene expression related to bone growth.

- Enhance vascularization (blood vessel formation).

This phenomenon is often called osteostimulation.

In simple terms, bioactiveglass does not just allow bone to grow—it encourages it.

Antibacterial Benefits in Orthopedic Applications

One of the most compelling advantages of certain bioactiveglass formulations is their antimicrobial potential.

When the material releases ions, it can:

- Increase local pH.

- Raise osmotic pressure.

- Create an environment unfavorable for bacterial growth.

This property is particularly valuable in treating bone infections such as osteomyelitis, a major concern in orthopedic surgery.

Unlike antibiotics, which bacteria can develop resistance to, the antibacterial effect of bioactiveglass is based on environmental change rather than chemical attack.

Forms of Bioactiveglass in Orthopedic Use

Bioactiveglass is highly versatile and can be manufactured in different forms:

- Granules – For filling bone voids.

- Putty or paste – For minimally invasive procedures.

- Porous scaffolds – Designed to mimic natural bone structure.

- Coatings on implants – To improve bone-implant integration.

- 3D printed structures – Customized for patient-specific defects.

This adaptability allows orthopedic surgeons to choose the right format depending on the clinical need.

Bioactiveglass in Orthopedic Procedures

1. Bone Defect Repair

In trauma cases or tumor resections, bone voids must be filled to restore structural integrity. Bioactiveglass granules can act as a scaffold while actively stimulating regeneration.

Over time, the material gradually dissolves and is replaced by natural bone.

2. Spinal Fusion

Spinal fusion requires bone growth between vertebrae to stabilize the spine. Bioactiveglass can support fusion by promoting osteoblast activity and enhancing bone bonding.

3. Infection Management

Certain compositions, such as S53P4 bioactiveglass, are used in managing chronic bone infections due to their antimicrobial environment-modifying properties.

4. Implant Coatings

Metal implants coated with bioactiveglass show improved osseointegration. This means the bone bonds more effectively with the implant, potentially reducing loosening over time.

Comparing Bioactiveglass with Traditional Orthopedic Materials

| Feature | Autograft | Ceramic | Metal | Bioactiveglass |

| Biological Activity | High | Low | None | High |

| Infection Control | Limited | Limited | None | Yes (Certain types) |

| Donor Site Required | Yes | No | No | No |

| Customizable | No | Limited | Limited | Yes |

| Direct Bone Bonding | Yes | Partial | No | Yes |

While no material is perfect, bioactiveglass addresses many of the biological gaps seen in traditional orthopedic solutions.

Limitations of Bioactiveglass

Scientific transparency is important.

Bioactiveglass also has limitations:

- It is brittle and not suitable alone for high load-bearing areas.

- Degradation rate must match healing pace.

- Manufacturing advanced scaffolds can be expensive.

- Long-term data in certain complex orthopedic applications is still evolving.

Because of this, it is often used in combination with other materials.

The Future of Bioactiveglass in Orthopedic Innovation

Research in this field continues to grow rapidly. Scientists are exploring:

- Ion-doped bioactiveglass (with strontium or zinc) to enhance bone formation.

- Composite materials combining glass with polymers for improved strength.

- 3D printing technologies for patient-specific implants.

- Smart coatings that release ions in response to biological signals.

The goal is clear: to create materials that communicate intelligently with the body.

Why Bioactiveglass Represents a Shift in Orthopedic Thinking

Traditional orthopedic materials focus on structure. Bioactiveglass focuses on biology.

It bridges the gap between mechanical support and biological stimulation. Instead of being a passive presence in the body, it actively participates in healing.

For patients, this may translate into:

- Improved bone regeneration.

- Reduced infection risk.

- Better integration with implants.

- Potentially shorter recovery times.

For surgeons, it offers flexibility and innovation.

For the future of orthopedic science, it represents a move toward regenerative solutions rather than purely structural repairs.

Conclusion

Orthopedic medicine has come a long way from simple mechanical fixation. While autografts, allografts, ceramics, and metal implants remain valuable tools, they each carry limitations in biological performance, infection control, and adaptability.

Bioactiveglass introduces a new dimension to orthopedic care. Backed by decades of biomaterials research, it chemically bonds with bone, stimulates cellular activity, and in some formulations, provides antibacterial benefits.

It is not merely a substitute material. It is a regenerative partner.

As research expands and technology advances, bioactiveglass is poised to become an increasingly important component of modern orthopedic solutions—supporting healing not just by holding bone together, but by helping the body rebuild itself.

The future of orthopedics may not lie in stronger metals or larger grafts, but in smarter materials that truly understand how bone heals.

Contact us through Synthera Biomedical social platforms to stay informed about pioneering bioactive glass research and clinical applications. Follow us on Instagram for product launches and research updates. Join the conversation on Facebook to access valuable resources and community news.

References:

1. Giannoudis, Peter V. et al. (November 2005), Bone substitutes: An update Injury, Volume 36, Issue 3, Supplement S20-S27.

2. Fillingham Y, Jacobs J (January 2016), Bone grafts and their substitutes. Bone Joint J.;98-B (1 Suppl A):6-9.

3. Kokubo T, Takadama H May (2006), How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials.;27(15):2907-15.

4. Baino F, Hamzehlou S, Kargozar S. (March 2018), Bioactive Glasses: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? J Funct Biomater. 19;9(1):25.

5. Jones JR. (Jan 2013),Review of bioactive glass: from Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater; 9(1):4457-86.