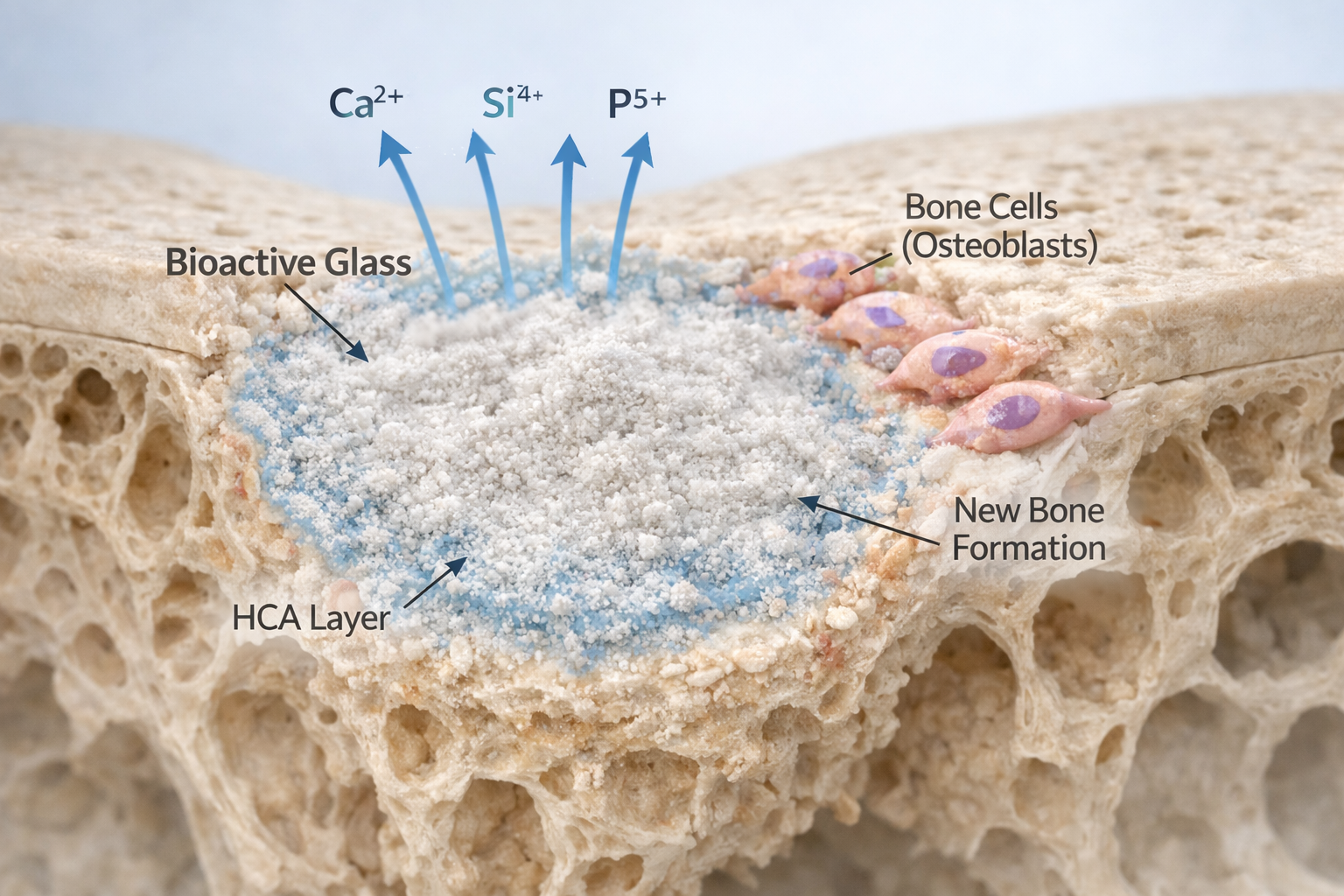

Bioactive glasses constitute a distinct class of amorphous inorganic materials capable of forming a strong interfacial bond with bone and soft tissues through the in situ development of a hydroxyapatite (HA) layer. Since the development of Hench’s 45S5 Bioglass® in 1969, understanding the thermal behaviour of these materials has been central to their successful processing and biomedical application. Thermal analysis techniques, particularly Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA), have provided critical insight into how bioactive glass compositions respond to heating, structural relaxation, and crystallization.

Among available thermoanalytical methods, DTA remains a robust and informative approach for evaluating phase transformations and thermal stability in bioactive glasses. This article presents a scientifically rigorous overview of the principles of DTA, the characteristic thermal events observed in bioactive glass systems, and the relevance of these findings to processing strategies and biomedical performance.¹

Fundamentals of Differential Thermal Analysis

Differential Thermal Analysis is based on measuring the temperature difference between a sample and an inert reference material as both are subjected to a controlled heating or cooling programme. When the sample undergoes an endothermic or exothermic event—such as glass transition, crystallization, or melting—a deviation in temperature relative to the reference is recorded.

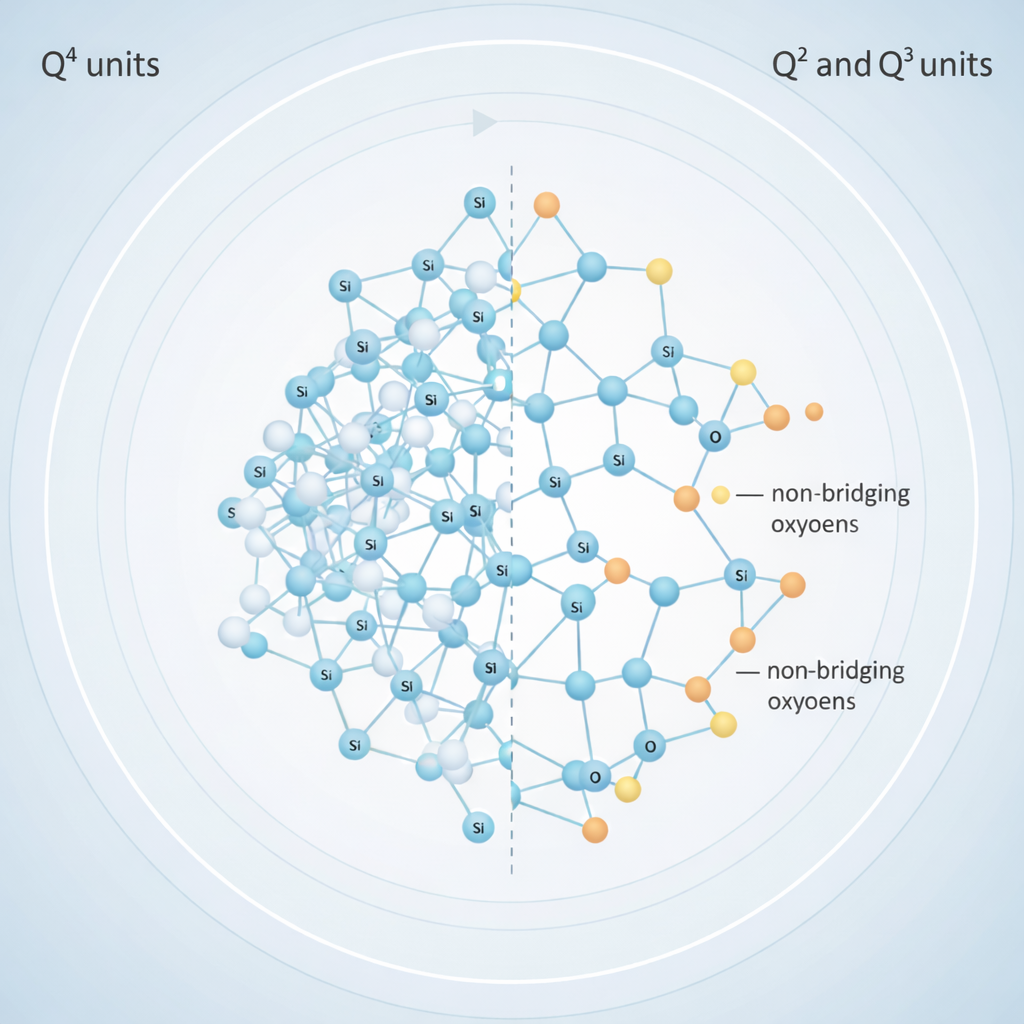

For glassy materials, thermal behaviour is intrinsically linked to structural characteristics including network connectivity, modifier concentration, and the presence of non-bridging oxygens. In bioactive glasses, these features govern not only thermal stability but also processability and bioactivity. As many bioactive glass compositions possess narrow sintering windows and pronounced crystallization tendencies, DTA plays a particularly important role in defining safe and effective thermal processing conditions for biomedical forms such as scaffolds, fibres, coatings, and granules.¹

Characteristic Thermal Events in DTA of Bioactive Glass

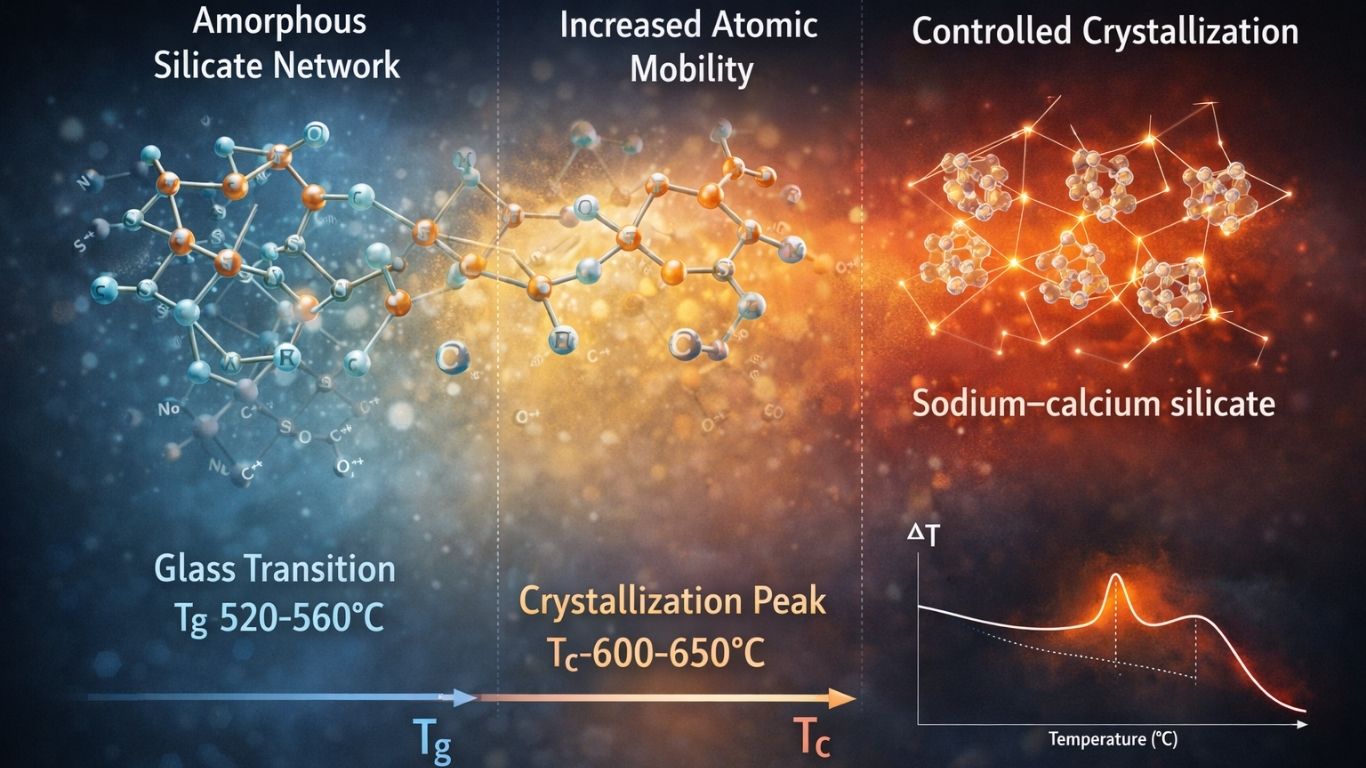

A typical DTA profile of a silicate-based bioactive glass reveals three principal thermal events: the glass transition temperature (Tg), one or more crystallization temperatures (Tc), and the melting temperature (Tm). Each of these events corresponds to specific atomic-scale processes within the amorphous network.¹

Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

The glass transition appears in DTA as a subtle endothermic shift in the baseline, marking the temperature range over which the rigid glass structure gradually transforms into a more mobile, viscoelastic state. At the atomic level, this transition reflects increased mobility of silicate network segments and modifier cations such as Na⁺ and Ca²⁺.

For 45S5 Bioglass®, the glass transition temperature typically falls within the range of 520–560 °C. Tg is strongly influenced by network connectivity; increased disruption of the silicate network—commonly associated with higher alkali oxide content—results in a lower Tg. From a processing standpoint, Tg represents the minimum temperature at which viscous flow becomes possible. Consequently, understanding Tg is essential for thermal treatments such as sintering or fibre drawing, which must be conducted above Tg but below the onset of crystallization to preserve amorphous structure and bioactivity.²

Crystallization Temperature (Tc)

With continued heating, bioactive glasses exhibit one or more exothermic peaks in the DTA curve corresponding to crystallization of the amorphous matrix. This exothermic event arises from the release of latent heat as ordered crystalline phases nucleate and grow.

In classical 45S5 glass, the primary crystallization temperature is commonly observed in the range of 600–650 °C and is often associated with the formation of sodium–calcium silicate phases such as Na₂Ca₂Si₃O₉.³ The crystallization behaviour, as reflected by the shape and number of exothermic peaks, provides valuable insight into crystallization kinetics:

- A single sharp peak indicates rapid, one-step crystallization

- Multiple peaks suggest multi-stage crystallization or formation of several phases

- Broad peaks imply sluggish crystallization kinetics and enhanced thermal stability

The temperature difference between glass transition and crystallization, expressed as ΔT = Tc − Tg, is widely used as an indicator of glass stability. A larger ΔT denotes a broader processing window, allowing thermal shaping above Tg without premature crystallization. Many Na₂O-rich bioactive glasses exhibit relatively small ΔT values, necessitating precise thermal control during sintering and scaffold fabrication.⁴–⁶

Melting Temperature (Tm)

At higher temperatures, DTA reveals a pronounced endothermic peak corresponding to melting or fusion of crystalline phases. For silicate-based bioactive glasses, melting temperatures typically exceed 1100 °C, although exact values depend on composition.

Analysis of melting behaviour offers insight into the thermal robustness of crystalline phases formed during heat treatment and informs the design of melt-quenching synthesis routes. Knowledge of Tm is therefore essential for both laboratory-scale glass preparation and industrial-scale manufacturing.⁷⁻⁸

Effect of Glass Composition on DTA Behaviour

One of the defining advantages of bioactive glasses is their compositional tunability. Even modest changes in oxide content can significantly alter thermal behaviour, as reflected in DTA profiles.

Influence of Network Modifiers

Alkali and alkaline earth oxides such as Na₂O, K₂O, CaO, and MgO act as network modifiers by breaking silicate bonds and generating non-bridging oxygens. This depolymerization typically results in:

- Reduced glass transition temperature

- Increased tendency toward crystallization

- Narrower processing windows

For instance, elevated Na₂O content lowers Tg to such an extent that viscous flow sintering may overlap with crystallization, complicating the fabrication of porous scaffolds with retained amorphous character.⁹

Role of Network Formers and Intermediate Oxides

Oxides such as B₂O₃, P₂O₅, and TiO₂ can function as network formers or intermediates, modifying bonding environments within the glass. Their incorporation often leads to:

- Increased Tg and Tc

- Broader ΔT values, indicating improved thermal stability

- Altered crystallization pathways

- Modified bioactivity and dissolution behaviour

Such compositional adjustments allow researchers to tailor thermal and biological performance simultaneously.¹⁰

Impact of Functional Ion Doping

The incorporation of therapeutic or antibacterial ions—including Sr²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Ag⁺—also influences thermal events observed in DTA. Depending on their structural role, these dopants may act as network modifiers or intermediates, resulting in measurable shifts in Tg and Tc.

For example, ZnO is known to enhance glass stability by increasing ΔT, whereas Ag₂O typically reduces Tg due to its network-modifying behaviour. These thermal effects must be carefully considered when designing multifunctional bioactive glasses for biomedical use.¹¹

Importance of DTA in Bioactive Glass Processing and Biomedical Applications

Optimizing Sintering and Scaffold Fabrication

A major challenge in processing 45S5 bioactive glass lies in the proximity of its sintering temperature to its crystallization temperature. DTA enables identification of a narrow “safe” thermal window where viscous flow sintering can occur without inducing crystallization. Processing within this window preserves the amorphous structure essential for high bioactivity.²

Controlled Crystallization for Glass–Ceramics

In applications requiring enhanced mechanical strength, such as load-bearing implants, controlled crystallization may be desirable. DTA-guided heat treatments allow precise induction of specific crystalline phases, resulting in bioactive glass–ceramics that combine improved mechanical performance with retained biological activity.²

Linking Structure to Properties

Beyond processing guidance, DTA contributes to a deeper understanding of structure–property relationships in bioactive glasses. Interpretation of Tg, Tc, and Tm provides insight into network connectivity, ion mobility, and thermochemical stability—parameters that directly influence dissolution rate, mechanical behaviour, bioactivity, and antibacterial performance.¹²

Conclusion

Differential Thermal Analysis remains an essential technique for the characterization and engineering of bioactive glasses. By accurately identifying glass transition, crystallization, and melting temperatures, DTA enables optimization of processing conditions, assessment of thermal stability, and informed compositional design. As research continues to expand toward multifunctional bioactive glasses incorporating therapeutic ions, DTA will remain central to understanding and controlling their complex thermal behaviour, ultimately supporting the advancement of next-generation biomedical materials.

Contact us through Synthera Biomedical social platforms to stay informed about pioneering bioactive glass research and clinical applications. Follow us on Instagram for product launches and research updates. Join the conversation on Facebook to access valuable resources and community news.

Refernce :

1. Arstila, H., Vedel, E., Hupa, L., Ylänen, H., & Hupa, M. (2006). Measuring the devitrification of bioactive glasses. In Key Engineering Materials (Vols. 254–256, pp. 67–72). Trans Tech Publications. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.254-256.67

2. Lefebvre, L., Chevalier, J., Gremillard, L., Zenati, R., Thollet, G., Bernache-Assolant, D., & Govin, A. (2007). Structural transformations of bioactive glass 45S5 with thermal treatments. Acta Materialia, 55(10), 3305–3313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2007.01.029

3. Hench, L. L. (1991). Bioceramics: From concept to clinic. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 74(7), 1487–1510.

4. Hench, L. L., & Wilson, J. (1993). An Introduction to Bioceramics. World Scientific Publishing.

5. Zhang, Y., & Greer, A. L. (2004). Crystallization kinetics of bioactive glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 345–346, 509–513.

6. Ray, C. S., Huang, W., & Day, D. E. (2001). Thermal behavior of bioactive glasses. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 84(2), 363–368.

7. Varshneya, A. K. (1994). Fundamentals of Inorganic Glasses. Academic Press.

8. Shelby, J. E. (2005). Introduction to Glass Science and Technology. Royal Society of Chemistry

9. Lefebvre, L., Chevalier, J., Gremillard, L., Zenati, R., & Bernache-Assollant, D. (2007). Structural transformations of bioactive glass 45S5 with thermal treatments. Acta Biomaterialia, 3(1), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2006.09.004

10. Brückner, R., Yue, Y., & Deubener, J. (2016). Crystallization and thermal stability of oxide glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 451, 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2016.07.001

11. Aina, V., Cerrato, G., Martra, G., Malavasi, G., & Lusvardi, G. (2019). Zinc-containing bioactive glasses: Surface reactivity and antibacterial properties. Journal of Materials Science, 54(6), 4988–5003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-03279-2

12. Jones, J. R. (2013). Review of bioactive glass: From Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomaterialia, 9(1), 4457–4486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.023