A deep scientific dive for professionals, researchers, and anyone curious about how bioactive glass truly interacts with the human body.

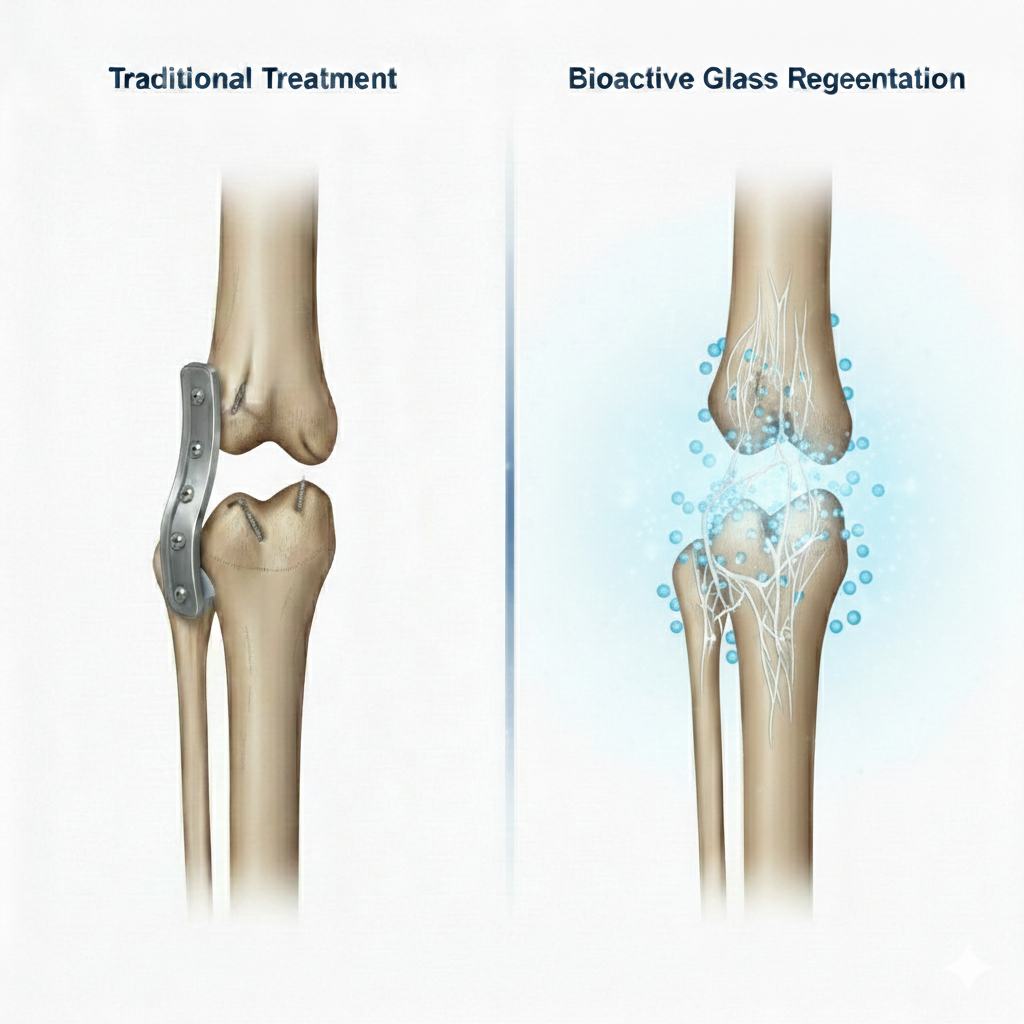

Bioactive glass has earned a reputation in materials science and regenerative medicine for one powerful reason: it communicates with the body. Unlike inert biomaterials that simply “exist” inside tissues, bioactive glass actively participates in healing by releasing ions that stimulate biological processes. Whether the goal is bone repair, soft-tissue enhancement, or advanced regenerative therapies, ion release is the first and most important step in the chain of events that gives bioactive glass its bioactivity.

In our laboratory—and in countless studies worldwide—measuring the release of ions from bioactive glass has become a critical method to understand its behaviour, predict biological performance, and engineer improved formulations. This blog breaks down the science, the methods, and the significance of ion release in a structured, research-style way while making the concepts approachable to a wider audience.

1. Why Ion Release Matters in Bioactive Glass

Bioactive glass is not a passive material. The moment it enters a physiological environment—whether in simulated body fluid (SBF), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or cell culture medium—it undergoes a controlled degradation process. This isn’t material failure; in fact, it is the very mechanism that allows bioactive glass to bond with tissue and stimulate regeneration.

The first steps at the glass–solution interface

When bioactive glass interacts with any physiological fluid, an ion-exchange reaction begins almost instantly:

-

- Alkali ions such as Na⁺ and K⁺ leave the glass.

-

- Alkaline-earth ions like Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ diffuse out.

-

- These ions are replaced by H⁺ or H₃O⁺ from the environment.

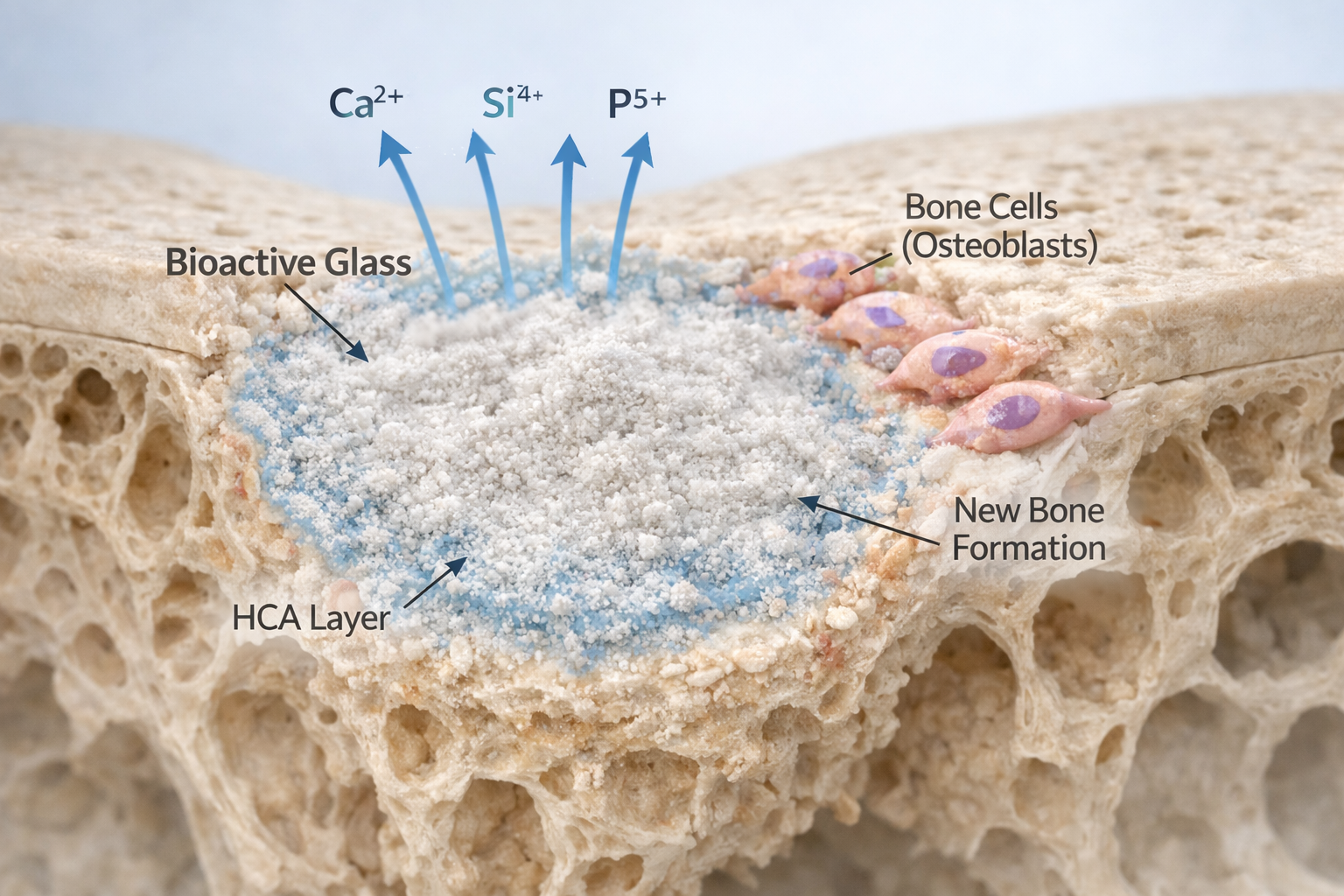

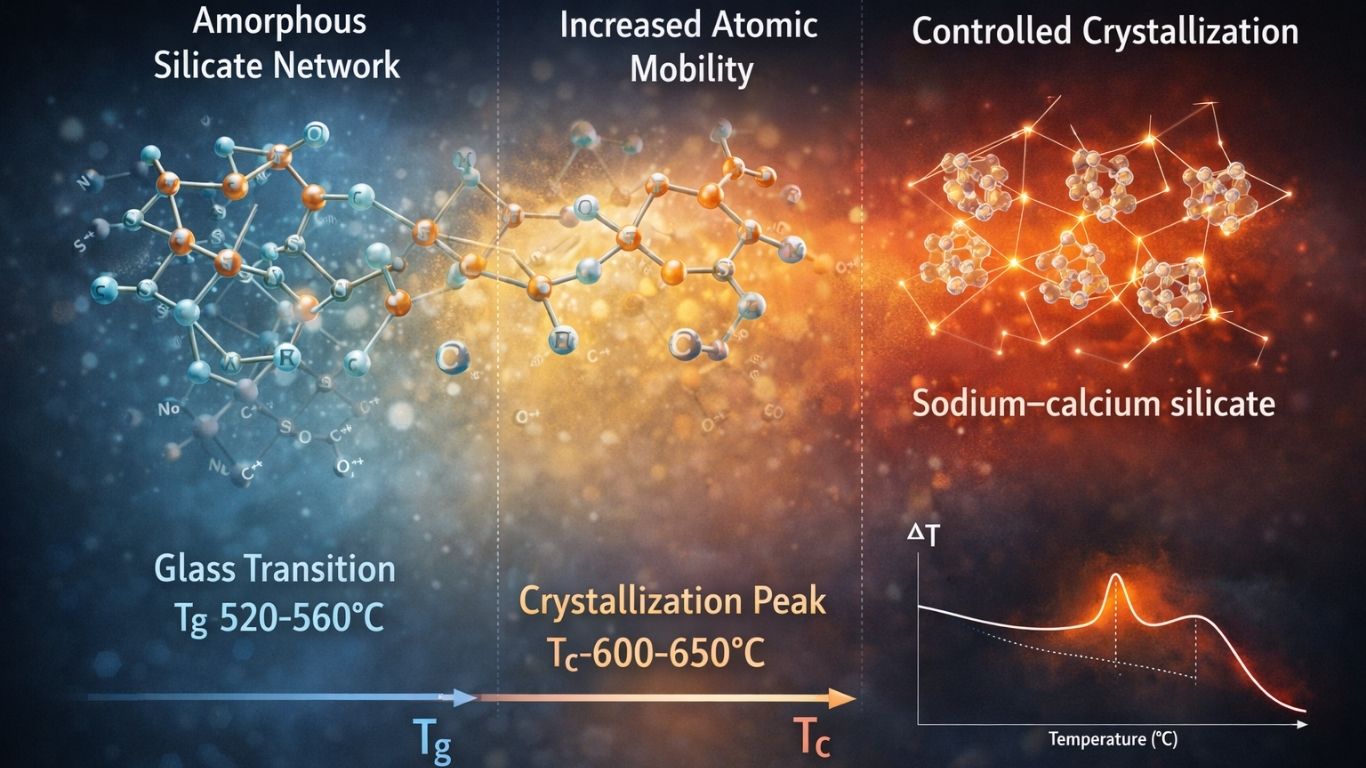

This exchange acidifies the surface structure and transforms the glass network. The original silicate network breaks down and reorganizes into silanol groups (Si–OH), forming a hydrated silica gel layer. Shortly after, calcium and phosphate migrate to the surface, creating an amorphous calcium-phosphate layer. With time, this layer crystallizes into hydroxyapatite, the mineral phase that makes up natural bone.

Why this matters biologically

The ions released—especially Si⁴⁺, Ca²⁺, P⁵⁺, Na⁺, and Mg²⁺—act like chemical messengers. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that these ions:

-

- stimulate stem cell proliferation

-

- trigger osteogenic differentiation

-

- enhance extracellular matrix production

-

- support mineralization

In simple terms, the biological performance of bioactive glass directly depends on what ions are released, in what quantity, and how fast.

2. How Ion Release from Bioactive Glass Is Measured

Measuring ion release is a multi-step process that involves controlled immersion experiments and highly sensitive analytical instruments. This ensures that the data accurately reflects what the material does inside the body.

Below, I’m presenting the workflow in a clear research-style structure, similar to how we follow it in real laboratory environments.

3. Sample Preparation: Setting Up the Bioactive Glass for Testing

Bioactive glass can be prepared in several forms—powders, particles, scaffolds, or dense monoliths. The geometry matters, because surface area directly affects dissolution rate.

Two most common sample types:

-

- Powders

-

- A defined mass (e.g., 50 mg, 100 mg) is weighed precisely.

-

- Powders dissolve faster due to high surface area.

-

- Powders

-

- Bulk and Scaffold Samples

-

- Cut to consistent dimensions to ensure experimental reliability.

-

- Often preferred when mimicking clinical or tissue engineering scenarios.

-

- Bulk and Scaffold Samples

All samples are sterilised when ion-release experiments connect to biological or cell studies.

4. Immersion Media and Conditions

Bioactive glass is typically immersed in one of three fluids depending on the test objective:

1. Simulated Body Fluid (SBF)

Used to mimic ionic composition of human plasma.

2. Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Stable pH-buffered environment to isolate dissolution kinetics.

3. Cell Culture Medium

Used when the objective is to correlate ion release with biological outcomes.

Key experimental controls:

-

- Temperature: 37 °C

-

- Agitation: gentle shaking to mimic physiological motion

-

- Solution-to-solid ratio: carefully selected to prevent ion saturation

Maintaining these conditions ensures consistency across time points and reproducibility.

5. Sampling and Collection of Supernatant

Ion release studies involve collecting small fluid samples over time while keeping experimental volume constant.

Typical time points include:

-

- 1 hour, 6 hours,24 hours,3 days,7 days,14 days,21 days

At each interval:

-

- A fixed volume is removed.

-

- The same volume of fresh medium is added back.

-

- Samples are filtered or centrifuged to remove particles.

-

- Supernatants are stored at low temperatures until analysis.

I can tell from experience that even small lapses here—like inconsistent pipetting or contamination—can interfere with analytical results. Precision is key.

6. Analytical Methods: How Each Ion Is Quantified

Once samples are collected, the next step is to analyse the concentration of ions released from the bioactive glass.

The two gold-standard techniques are:

A. ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy)

-

- Detects elements based on emission wavelengths of excited atoms.

-

- Excellent for multi-element detection (Si, Ca, P, Na, Mg, K).

-

- Rapid and reliable.

B. ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry)

-

- Measures ions based on mass-to-charge ratio.

-

- Extremely sensitive (down to parts per billion).

-

- Preferred when studying subtle changes in dissolution.

Other techniques occasionally used:

-

- Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) for targeted ions

-

- Ion Chromatography (IC) for soluble silica

-

- UV–Vis spectroscopy for phosphate or silica depending on assay design

Before analysis, samples are usually diluted with nitric acid (HNO₃) to ensure they fall within instrument calibration ranges.

Calibration standards are prepared for every element. Instrument parameters such as plasma power, nebulizer flow, and wavelength selection are optimized for maximum accuracy.

7. Data Analysis: Understanding the Ion Release Profile

Ion concentrations are typically expressed as:

-

- mg/L (milligrams per litre)

-

- ppm (parts per million)

Researchers then calculate cumulative release and plot the values against time.

Typical ion-release behaviour of bioactive glass:

Early stage (first 24 hours)

-

- Rapid release of Na⁺ and Ca²⁺

- Rapid release of Na⁺ and Ca²⁺

-

- Happens due to fast ion exchange at the surface

-

- Causes a rise in pH

Intermediate stage (days 2–7)

-

- Progressive release of Si⁴⁺

- Progressive release of Si⁴⁺

-

- Indicates breakdown of the silica network

-

- Important for osteogenic stimulation

Late stage (7+ days)

-

- Release of P⁵⁺ aligned with formation of calcium-phosphate layer

-

- Signals onset of hydroxyapatite crystallization

This profile is widely considered a signature of high-quality bioactive glass.

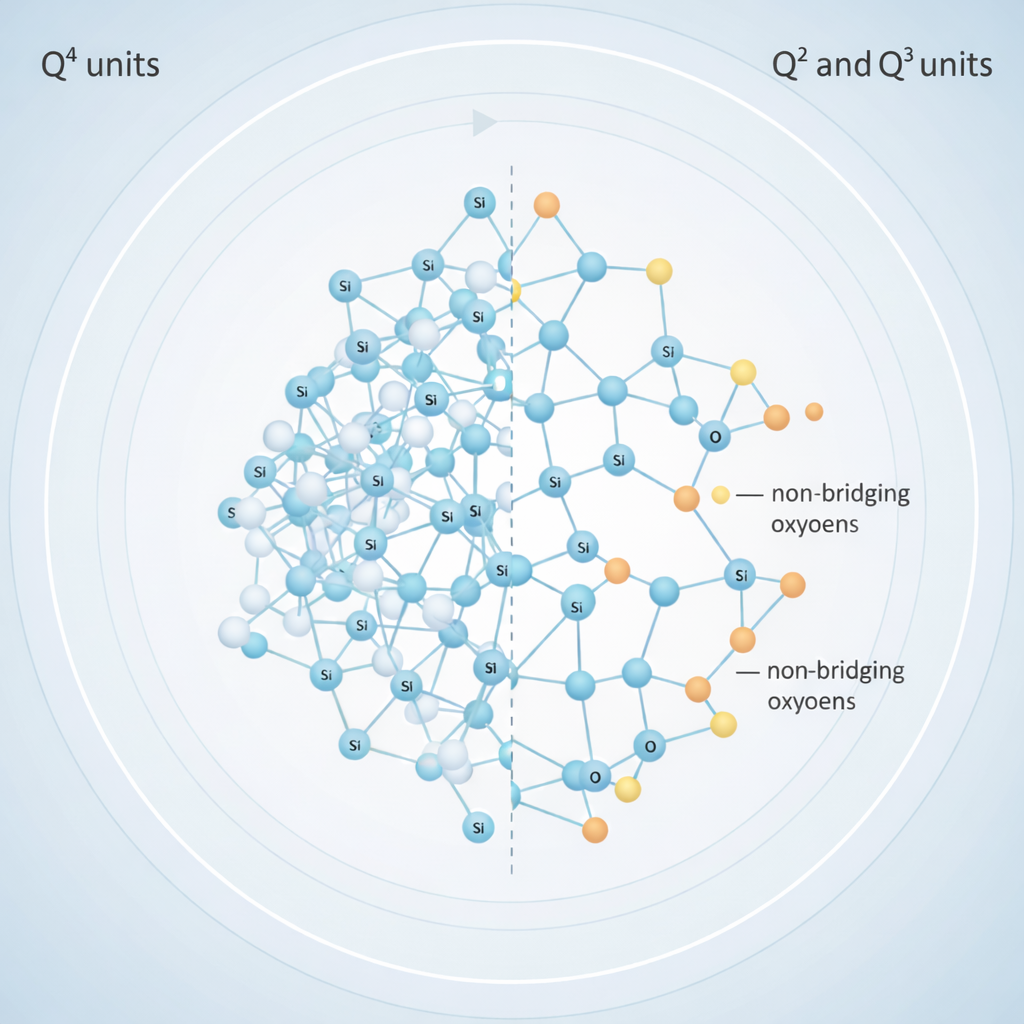

8. How Glass Composition Affects Ion Release

Not all bioactive glass compositions behave the same way. SiO₂ content, network modifiers, particle size, and porosity all shape dissolution kinetics.

Lower silica content

-

- Faster dissolution

-

- Higher ion release

-

- Stronger short-term bioactivity

-

- But may reduce mechanical stability and longevity

Higher porosity

-

- More surface area

-

- Higher ion exchange rate

Presence of modifiers (Na₂O, CaO, MgO, K₂O)

-

- Determines how easily the network can break down

These variables must be optimized depending on the intended application—bone repair vs soft-tissue regeneration often require different dissolution speeds.

9. Why Correlating Ion Release with Cell Response Is Essential

Researchers increasingly recognize that bioactive glass is not merely a mineral donor. The ions act as signaling cues that change how cells behave.

Silicon ions (Si⁴⁺):

-

- Stimulate osteogenic gene expression

-

- Encourage extracellular matrix formation

Calcium ions (Ca²⁺):

-

- Crucial for mineral nucleation

-

- Influence ECM mineralization rates

-

- Support cell differentiation pathways

Phosphate ions (P⁵⁺):

-

- Form the mineral phase

-

- Help stabilize hydroxyapatite formation

This is why ion-release data is often paired with biological assays like:

-

- ALP (alkaline phosphatase) activity

- ALP (alkaline phosphatase) activity

-

- RUNX2 and OPN expression

- RUNX2 and OPN expression

-

- Alizarin Red S mineralization

- Alizarin Red S mineralization

Together, they provide a comprehensive picture of bioactive glass performance.

10. Common Pitfalls in Ion-Release Experiments

From observing real lab setups, I’ve learned that several factors often lead to misleading results:

1. Solution saturation

If the ratio of solution to sample is too low, released ions may hit solubility limits, giving an artificially low reading.

2. pH drift

Bioactive glass increases pH. If pH rises too far, dissolution changes drastically. Monitoring pH alongside ion release is essential.

3. Contamination from labware

Glass containers, improperly cleaned pipette tips, or metal tools can introduce background ions.

4. Medium complexity

Cell culture media contain many ions already. Using matrix-matched standards avoids incorrect calibration.

5. Inconsistent sample sizes

Variations in mass or surface area create misleading comparisons.

A method is only as good as its controls. And in ion-release studies, controls are everything.

11. Interpretation: What Ion Release Tells Us About Bioactive Glass

The goal of measuring ion release is not just to collect numbers—it is to understand how the bioactive glass behaves biologically.

Strong ion release typically means:

-

- High bioactivity

-

- Faster hydroxyapatite formation

-

- Strong potential for bone bonding

Moderate, controlled ion release suggests:

-

- Balanced regeneration

-

- Suitable for softer tissues

-

- Reduced risk of excessive pH rise

Ultimately, ion release is a window into the future behaviour of the material.

12. Conclusion

Bioactive glass is one of the most fascinating and impactful materials in regenerative medicine. Its ability to dissolve in a controlled manner and release biologically active ions makes it uniquely capable of stimulating healing rather than simply serving as a passive support.

Measuring ion release provides the foundational evidence needed to understand dissolution behaviour, optimize material design, evaluate bioactivity, and connect material performance with cellular outcomes. Whether you are a student just discovering the field, a healthcare professional exploring biomaterials, or a scientist developing the next generation of regenerative technologies, ion release remains the most direct way to evaluate what bioactive glass truly offers.

This blog has walked through the key mechanisms, experimental methods, analytical tools, and interpretations associated with ion release from bioactive glass—presented in a professional, authoritative, yet human tone. Part II will explore correlating ion-release data with cellular outcomes and advanced characterizations.

Contact us through Synthera Biomedical social platforms to stay informed about pioneering bioactive glass research and clinical applications. Follow us on Instagram for product launches and research updates. Join the conversation on Facebook to access valuable resources and community news.

References

- Miguez-Pacheco, V., Hench, L. L., & Boccaccini, A. R. (2015). Acta Biomaterialia.

- Rohanová, D., Horkavcová, D., Boccaccini, A. R., & Helebrant, A. (2020). Review of acellular immersion tests.

- Dana Rohanová, Diana Horkavcová (2015). Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids.

- Shah, F. A., & Brauer, D. S. (2017). Journal of Materials Chemistry B.

- Galusková D.; Kaňková, H.; Švančárková, A.; Galusek, D. (2021). Materials.

- Nommeots-Nomm, A., et al. (2020). Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology.