Understanding the Science Behind Dissolution, Therapeutic Ions, and Analytical Methods

Bioactive glass is one of the most influential materials in modern regenerative medicine. Its ability to dissolve in physiological environments and release therapeutic ions is the very foundation of its bioactivity. These ions — calcium, silicon, phosphorus, and sometimes dopants such as strontium or magnesium — do far more than simply enter the surrounding fluid. They actively trigger cellular processes related to tissue healing, bone formation, and vascularization.

Because of this, studying ion release is not an optional research step; it is the central scientific indicator of how a bioactive glass will behave in a biological environment. Measuring ion release accurately allows researchers to evaluate degradation rates, predict biological effects, and fine-tune compositions for specific medical applications.

This article expands on the mechanisms and methods involved in ion release, highlights why controlled release matters, and explains why ion chromatography remains one of the most reliable analytical tools for this work. It aims to make the science accessible without oversimplifying — providing clarity even for readers outside the biomaterials field.

What Happens When Bioactive Glass Meets Physiological Fluid?

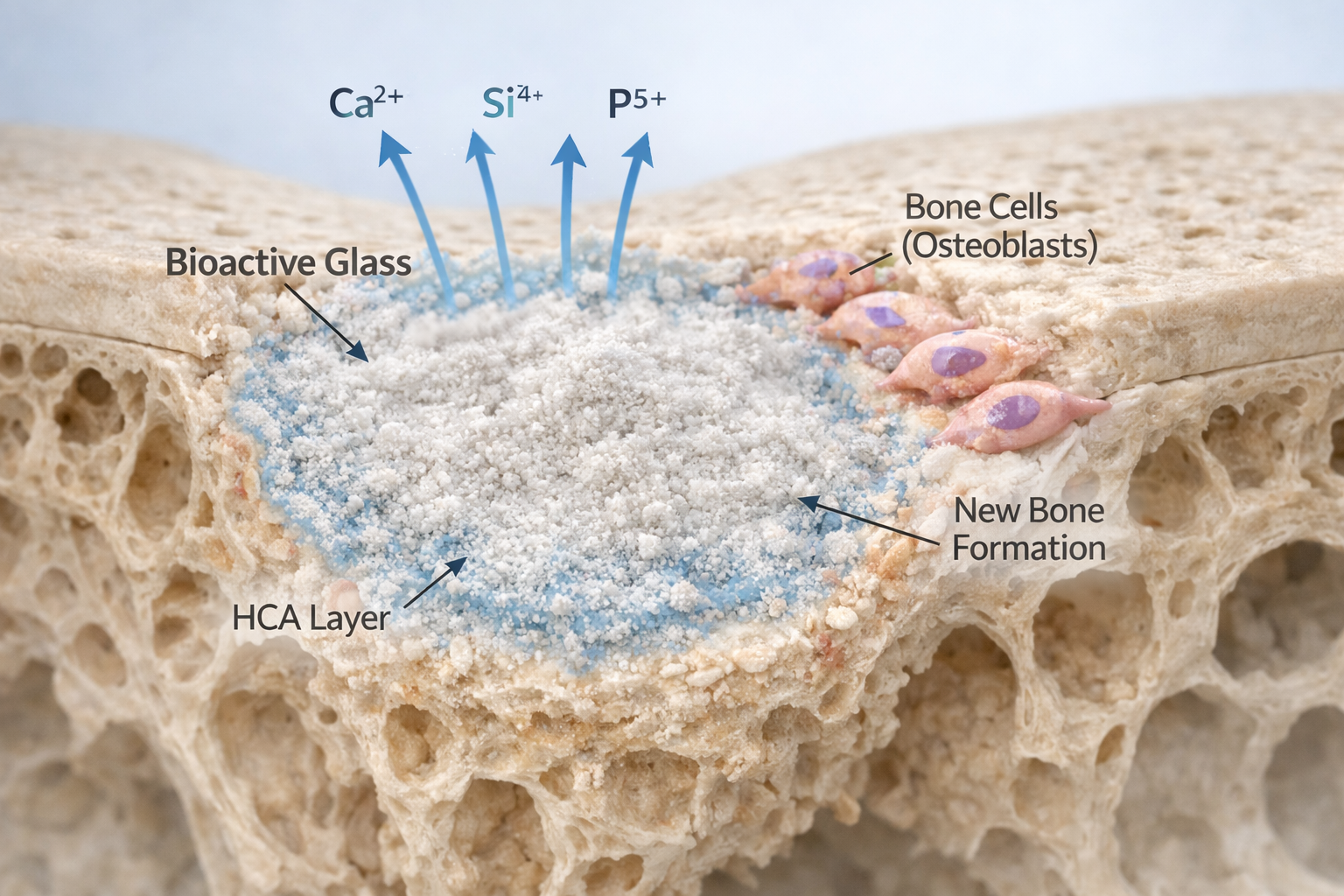

The ion release process begins the moment bioactive glass particles come into contact with aqueous solutions such as body fluids, cell culture media, or simulated body fluid (SBF). Although the chemistry is complex, it follows a sequence that has been repeatedly validated by decades of research.

1. Initial Ion Exchange (Milliseconds to Minutes)

The first step involves a rapid exchange between alkali ions (Na⁺, K⁺) embedded in the glass and hydronium ions (H₃O⁺) from the surrounding fluid.

- Na⁺ or K⁺ ions leave the glass

- H₃O⁺ ions from the solution diffuse into the glass network

This reaction increases the pH of the surrounding solution and weakens the silica network by breaking Si–O bonds.

2. Network Breakdown and Release of Therapeutic Ions (Minutes to Hours)

The destabilization of the glass network allows water molecules to penetrate deeper. This leads to the release of:

- Calcium ions (Ca²⁺)

- Phosphate species

- Soluble silica (often present as Si(OH)₄)

- Dopants when present: Sr²⁺, Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Li⁺, etc.

Each of these ions carries specific biological roles. For instance:

- Calcium supports signaling pathways essential for bone mineralization.

- Silicon is linked to collagen formation and osteogenic gene expression.

- Strontium has dual action: increases osteoblast activity while reducing osteoclast activity.

3. Formation of Hydroxyapatite Layer (Hours to Days)

As Ca²⁺ and phosphate accumulate, amorphous calcium phosphate forms on the glass surface, gradually crystallizing into hydroxyapatite (HA) — a mineral nearly identical to human bone.

This layer is what gives bioactive glass its ability to bond directly to living bone.

How Glass Composition Determines Ion Release Behavior

One of the most important principles in bioactive glass science is that not all glass compositions dissolve the same way.

Researchers intentionally alter composition to:

- Control dissolution speed

- Modify therapeutic ion release

- Enhance biological effects

- Improve mechanical or handling properties

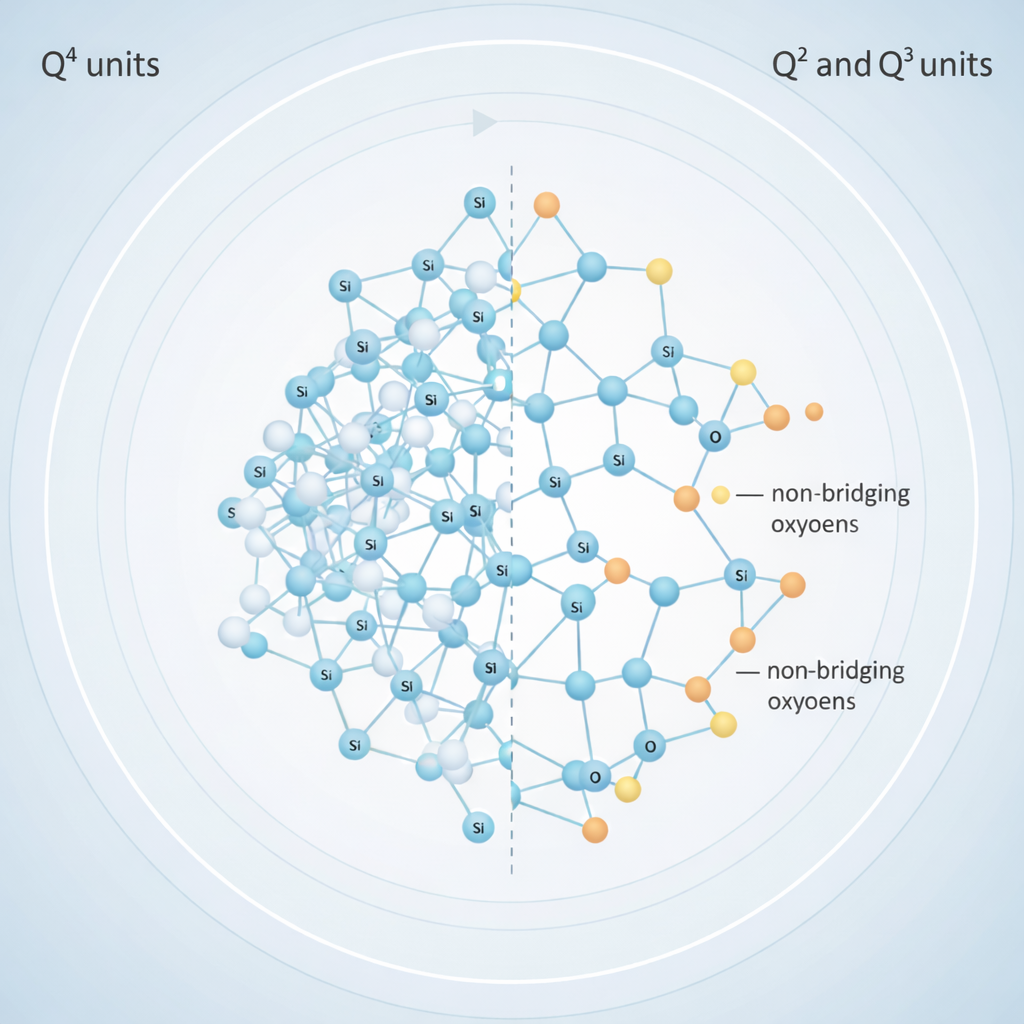

Role of Ionic Radius and Network Modifiers

Studies have shown that changing alkali or alkaline-earth ions significantly influences the silica network’s packing density and connectivity.

- Larger ions (K⁺, Sr²⁺):

Create more open networks → faster water penetration → accelerated ion release. - Smaller ions (Li⁺):

Compact the network → slower dissolution and lower initial release.

This is why glasses containing strontium or potassium may dissolve faster, while lithium-containing variants usually show more controlled, slower ion release profiles.

Molar Volume and Network Connectivity

Research from Brückner et al. demonstrates that both ionic radius and molar volume can predict how readily a glass will release ions. A glass with a higher molar volume introduces more structural free space, making it easier for fluids to diffuse into the matrix.

Understanding these chemical relationships enables scientists to design glasses tailored for:

- Faster release (e.g., wound healing)

- Moderate release (e.g., bone grafts)

- Highly controlled release (e.g., dental liners, restorative cements)

Why Ion Release Matters for Biological Performance

Ion release is not simply a chemical phenomenon — it directly impacts how cells behave around bioactive glass.

1. Stimulating Bone Growth (Osteogenesis)

Calcium and silicon ions promote:

- Expression of osteogenic markers such as RUNX2 and osteopontin

- ALP (alkaline phosphatase) activity

- Formation of mineralized bone matrix

Strontium ions further amplify osteoblast activity while reducing bone resorption.

2. Supporting Blood Vessel Formation (Angiogenesis)

Silicon and boron (in certain glasses) have been shown to stimulate endothelial cells and VEGF expression, contributing to improved vascularization — a crucial step in wound healing and bone repair.

3. Enhancing Wound Healing

Certain therapeutic ions strengthen fibroblast activity and improve collagen deposition. This is why bioactive glass has been explored in wound care, soft-tissue repair, and antimicrobial applications.

4. Controlling pH and Antibacterial Effects

The ion exchange process temporarily increases pH. In controlled amounts, this contributes to:

- Reduced bacterial growth

- Enhanced local environment for tissue regeneration

However, excessive alkalinity can harm cells, which is why understanding dissolution kinetics is essential.

Ion Chromatography: A Reliable Tool for Measuring Ion Release

Ion chromatography (IC) remains one of the most precise and sensitive techniques to quantify dissolved ions in fluid. For bioactive glass research, its ability to detect multiple ions in very small concentrations makes it indispensable.

How Ion Chromatography Works

- A fluid sample containing ions is injected into a chromatography column packed with ion-exchange resin.

- Ions interact with the resin based on charge and ionic size.

- An eluent displaces them at different retention times.

- A detector converts each elution peak into a measurable signal.

- Calibration standards enable accurate concentration calculations.

IC can detect ions down to parts per billion (ppb), which is extremely useful when tracking slow or long-term dissolution.

Why IC Is Suitable for Bioactive Glass Research

1. Ability to Analyze Multiple Ions Simultaneously

Most bioactive glasses release:

- Na⁺, K⁺

- Ca²⁺

- Mg²⁺

- Sr²⁺

- Si(OH)₄

- Phosphate species

- Fluoride or chloride if present

IC systems can measure many of these in a single run, giving a complete picture of dissolution profiles.

2. Time-Resolved Release Kinetics

By taking samples at multiple time points — hours, days, weeks — IC creates detailed release curves showing:

- Burst release

- Sustained release

- Plateau phases

- Comparative dissolution between formulations

This data helps researchers refine compositions, particle sizes, and sintering conditions.

3. High Sensitivity for Trace Ions

Even dopants added in very small amounts (e.g., zinc, boron) can be detected and quantified.

4. Suitable for Complex Media

Bioactive glass may be studied in:

- Water

- PBS

- Cell culture media

- Simulated body fluid

- Saliva-like solutions

IC can function in all these environments with proper method optimization.

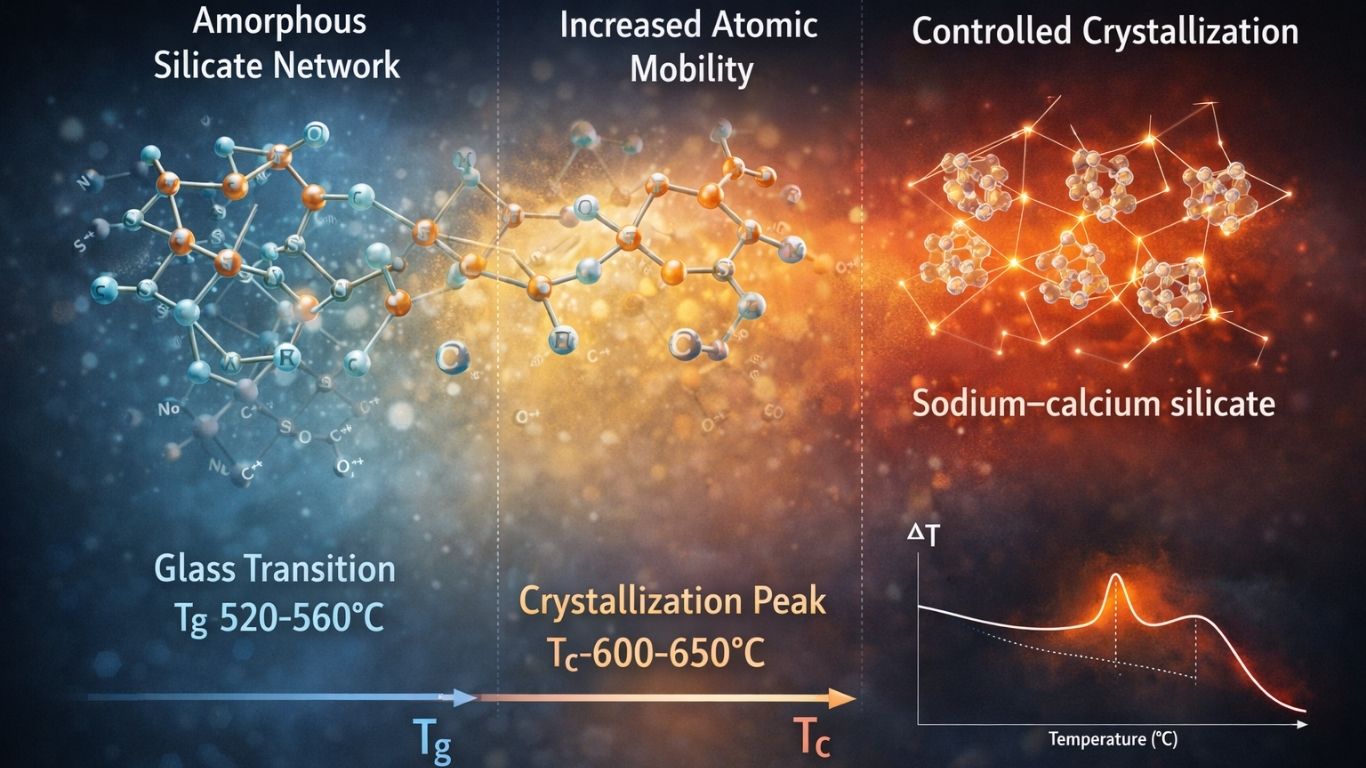

Importance of Controlling Ion Release

Not all clinical applications require the same release behavior. Controlling ion release ensures optimal biocompatibility and therapeutic effects.

Fast Release:

Useful in wound healing or antimicrobial applications where rapid ion delivery is beneficial.

Moderate Release:

Best for bone tissue engineering, where sustained delivery supports cell differentiation and mineralization.

Slow Release:

Ideal for dental liners, bone fillers, or scaffolds requiring prolonged structural integrity.

Factors influencing release include:

- Glass composition

- Network connectivity

- Dopant ionic radius

- Particle size

- Porosity

- Processing parameters (e.g., quenching speed, sintering temperature)

Engineering these variables provides researchers with a powerful way to tune therapeutic outcomes.

Applications of Ion-Releasing Bioactive Glass

1. Bone Regeneration

Bioactive glass promotes osteoblast differentiation and supports mineralized matrix formation, making it ideal for:

- Bone grafts

- Maxillofacial repair

- Orthopedic coatings

- 3D-printed scaffolds

2. Dental Applications

Bioactive glass has shown benefits in:

- Restorative cements

- Remineralization agents

- Pulp protection materials

- Liner/base materials

- Enamel repair formulations

Its controlled release improves microhardness and reduces demineralization.

3. Soft Tissue Repair and Wound Healing

Glasses doped with therapeutic ions can improve fibroblast growth, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis.

4. Antibacterial and Antimicrobial Use

Dopants such as silver, copper, or zinc enhance antimicrobial properties while maintaining biocompatibility.

Conclusion

Studying ion release is central to understanding and optimizing the performance of bioactive glasses. The dissolution behavior — from initial alkali exchange to silica network breakdown and hydroxyapatite formation — determines how effectively the material stimulates bone formation, soft tissue repair, and other biological responses.

Ion chromatography stands out as a powerful analytical technique for monitoring these processes with precision, allowing researchers to build detailed, time-resolved profiles of multiple ions simultaneously.

As research advances, the ability to control and tailor bioactive glass ion release continues to open new possibilities in regenerative medicine, dentistry, and therapeutic device design.

By combining scientific understanding with precise analytical tools, bioactive glass remains one of the most promising materials for the next generation of biomedical applications.

Contact us through Synthera Biomedical social platforms to stay informed about pioneering bioactive glass research and clinical applications. Follow us on Instagram for product launches and research updates. Join the conversation on Facebook to access valuable resources and community news.

Reference

1 Fuchs, M., Gentleman, E., Shahid, S., Hill, R. G., & Brauer, D. S. (2015). Therapeutic ion-releasing bioactive glass ionomer cements with improved mechanical strength and radiopacity. Frontiers in Materials, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2015.00063

2 Mehrabi, T., Mesgar, A. S., & Mohammadi, Z. (2020). Bioactive glasses: A promising therapeutic ion release strategy for enhancing wound healing. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 6(10), 5399–5430. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00528

3 Piatti, E., Miola, M., & Verné, E. (2024). Tailoring of bioactive glass and glass-ceramics properties for in vitro and in vivo response optimization: A review. Biomaterials Science, 12, 4546–4589. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3BM01574B

4 Albeshti R. Strontium Ions Release from Novel Bioactive Glass-Containing Glass Ionomer Cements: A Preliminary Study. 2024;8(2):278–285. https://doi.org/10.47705/kjdmr.248218

5 Brückner, R., Tylkowski, M., Hupa, L., & Brauer, D. S. (2016). Controlling the ion release from mixed alkali bioactive glasses by varying modifier ionic radii and molar volume. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 4(18),

6 Cattalini, J. P., García, J., Mouriño, V. S., & Lucangioli, S. E. (Year). Development and validation of a Capillary Zone Electrophoresis method for the determination of calcium in composite biomaterials. Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina; National Research Council (CONICET), Argentina.

7 Maaly T, Darweesh FA, Elnawawy MS. Ion Release, Microhardness and Enamel Demineralization Resistance of New Bioactive Restorative Materials. J Clin Exp Dent. 2025 Jun 1;17(6):e656-e664. doi: 10.4317/jced.62357. PMID: 40621142; PMCID: PMC12225766.

8 Jones JR, Ehrenfried LM, Saravanapavan P, Hench LL. Controlling ion release from bioactive glass foam scaffolds with antibacterial properties. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006 Nov;17(11):989-96. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0434-x. Epub 2006 Nov 22. PMID: 17122909.